I’m sure that you have heard about those who are skilled in martial arts working toward being awarded a black belt. It is a major accomplishment for any martial artist and represents years of hard work, dedication, and discipline.

And for some “umbraphiles” — those who have spent decades chasing total eclipses of the sun around the world — the upcoming eclipse of April 8 will offer (in my opinion) an opportunity to earn a black belt for eclipse chasing.

Let me explain. And while you’re at it, be sure to watch my total solar eclipse lecture below, given to the Rockland Astronomy Club on Feb. 23, 2024.

Related: What will it be like to experience the total solar eclipse 2024?

Eclipse reruns

It is an interesting phenomenon that an eclipse, whether of the sun or the moon, will repeat itself or “return.” Yet, to the layperson today, the entire situation regarding eclipse prediction is seemingly a haphazard pattern.

Not so for those who lived more than two millennia ago!

The beginnings of eclipse predictions might have been started by some unknown and long-forgotten Sumerians who set down, in the 23rd century B.C., a clay-tablet record of an eclipse of the moon as an isolated incident. And in 747 B.C., a series of such records was begun in Babylonia that continued for some centuries.

Astronomers in Assyria and Babylonia kept track of time by carefully observing the motions of the moon and the sun. By recording the details of solar and lunar eclipses, the accuracy of these measurements increased markedly. And as they studied the record of centuries of eclipses, a pattern began to emerge: Eclipses tend to repeat themselves at intervals of just over 18 years, though they recur at different localities on the Earth.

This eclipse cycle is called the saros — Greek for “repetition.” It is used even to this day to make predictions. A saros cycle can be defined as 18 years, 15 days and 8 hours, minus the number of bissextles (leap-years) that intervene between eclipses. In most cases, this is equal to either 18 years, 10 days and 8 hours or 11 days and 8 hours, since almost always five or four leap years, respectively, intervene with almost equal frequency.

Successive eclipses belonging to a given series are similar in type, terrestrial latitude of occurrence and duration. Because of the extra 8 hours (one-third of a day), each successive eclipse occurs about 120 degrees in longitude to the west of its predecessor.

The upcoming eclipse of April 8, 2024, belongs to saros number 139, to differentiate it from other saros series that have either ended, are still in progress, or have yet to begin. A solar eclipse with an even saros number takes place when the moon crosses the Earth’s orbital plane going from north to south (called the descending node), while one with an odd saros number (such as saros 139) takes place when the moon crosses the Earth’s orbital plane going from south to north (called the ascending node).

During the 18+ year interval of one saros, there are — on average — 42 solar eclipses. So, there are 41 representatives of different saros series that can come and go between the time that a specific member of an eclipse “family” takes its bow and its predecessor returns for an encore performance a little over 18 years later.

For many, it started in 1970

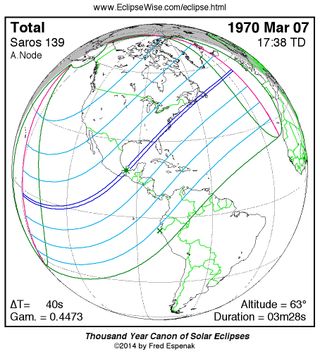

Many umbraphiles caught the eclipse chasing “bug” after witnessing their very first total solar eclipse on Saturday afternoon, March 7, 1970. On that occasion, the moon’s dark umbral shadow from where a total eclipse can be seen, moved across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in Mexico and into the Gulf of Mexico, then across northwestern Florida, Georgia, the Carolinas, and out into the Atlantic Ocean near Norfolk, Virginia.

After that, totality was observable from land on the island of Nantucket, Massachusetts, and from Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. The 1970 eclipse is a relative, so to speak, of the same saros family — 139 — that our upcoming April 8 belongs to.

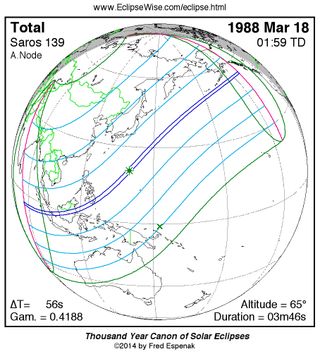

One saros cycle after 1970 — 18 years, 11 days and 8 hours later — on March 18, 1988, another member of saros family 139 made its appearance. Totality started in the Indian Ocean at local sunrise as the moon’s shadow touched down about 900 miles (1,400 km) west of Sumatra.

In just five minutes the shadow, traveling at 5.5 miles (8.8 km) per second, made landfall on the western shore of south Sumatra. The narrow patch of totality then arced to the northeast and turned day into night over central Borneo, and later, southern Mindanao in the Philippines. The shadow’s remaining path lay over the open waters of the North Pacific.

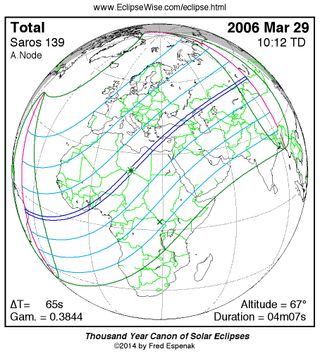

After another 18 years, 11 days and 8 hours, saros 139 returned on March 29, 2006, with totality sweeping across parts of West and North Africa, Turkey, and Central Asia. The moon’s dark shadow traced out a 9,000-mile (14,500-km) long track that varied in width from 78 to 118 miles (126 to 189 km).

Although this narrow track encompassed only 0.4 percent of Earth’s total surface area, those who were lucky enough to be positioned within it saw the sun get totally obscured for up to a little more than four minutes.

This leads us to the present, as another member of saros 139 is about to make its presence felt — as was the case in 1970 — again, over North America in less than a week, on April 8.

The “triple saros”

Now, after three saros repetitions, which is equal to 54 years and 33 ±1 days (since 13 ± 1 leap years respectively intervene, 33 days and 13 leap years being the most common) an eclipse recurs in the same general part of the world. We can call this a “triple saros” to describe this interval of time. American astronomer Owen Gingerich (1930-2023) noted that the Greeks called a period equal to three saros cycles an “Exeligmos” meaning the “Turning of the wheel.” For indeed, after three saros cycles, the moon’s shadow has wheeled completely around the Earth.

Study the similarities between the visibility zones of the March 7, 1970 eclipse compared one Exeligmos later to the upcoming April 8 eclipse.

And now, to earn a black belt in eclipse chasing, I propose that one would have to have traveled literally around the world to witness three previous members of the same saros family — in this case 139 — in 1970, 1988 and 2006, before completely “turning the wheel” by experiencing April’s eclipse and completing a triple saros:

- 1970-1988

- 1988-2006

- 2006-2024

This is, by no means an easy feat, for to do it, one will have to literally work their way around the globe following a specific saros series, taking more than 54 years to do it!

The term “black belt” is certainly appropriate when one considers that the moon’s dark umbral shadow itself tracks a black belt of darkness on its sweep across the Earth’s surface.

I myself will not be in the running for a black belt this year, as I did not experience my first total solar eclipse until July 10, 1972, at Cap-Chat, Quebec. That eclipse was a member of saros family 126. On July 21, 1990, I experienced another total eclipse from that same saros family on a commercial airline flight over the North Pacific Ocean, midway between Honolulu and San Francisco. When saros 126 returned on August 1, 2008, I viewed it from a chartered flight en route to circling over the North Pole. With luck, I am hoping to witness the total eclipse of August 12th, 2026, which will pass over Greenland, Iceland and the Iberian Peninsula, which would complete my personal triple saros and earn me a black belt in eclipse chasing.

Nothing lasts forever

A final point to note is that a saros family cannot last forever. Typically, a saros series contains 70 to 85 eclipses, lasting anywhere from 1,244 to 1,514 years. Series 139, with a total of 71 eclipses (16 partial, 12 annular-total or hybrid, and 43 total) began in the year 1501 and will come to an end in the year 2763, lasting from start to finish for a total of 1,262 years.