There was an electric moment on Feb. 22, when Intuitive Machines’ Odysseus lander, a rectangular prism built atop several slender metallic legs, touched down on the surface of the moon.

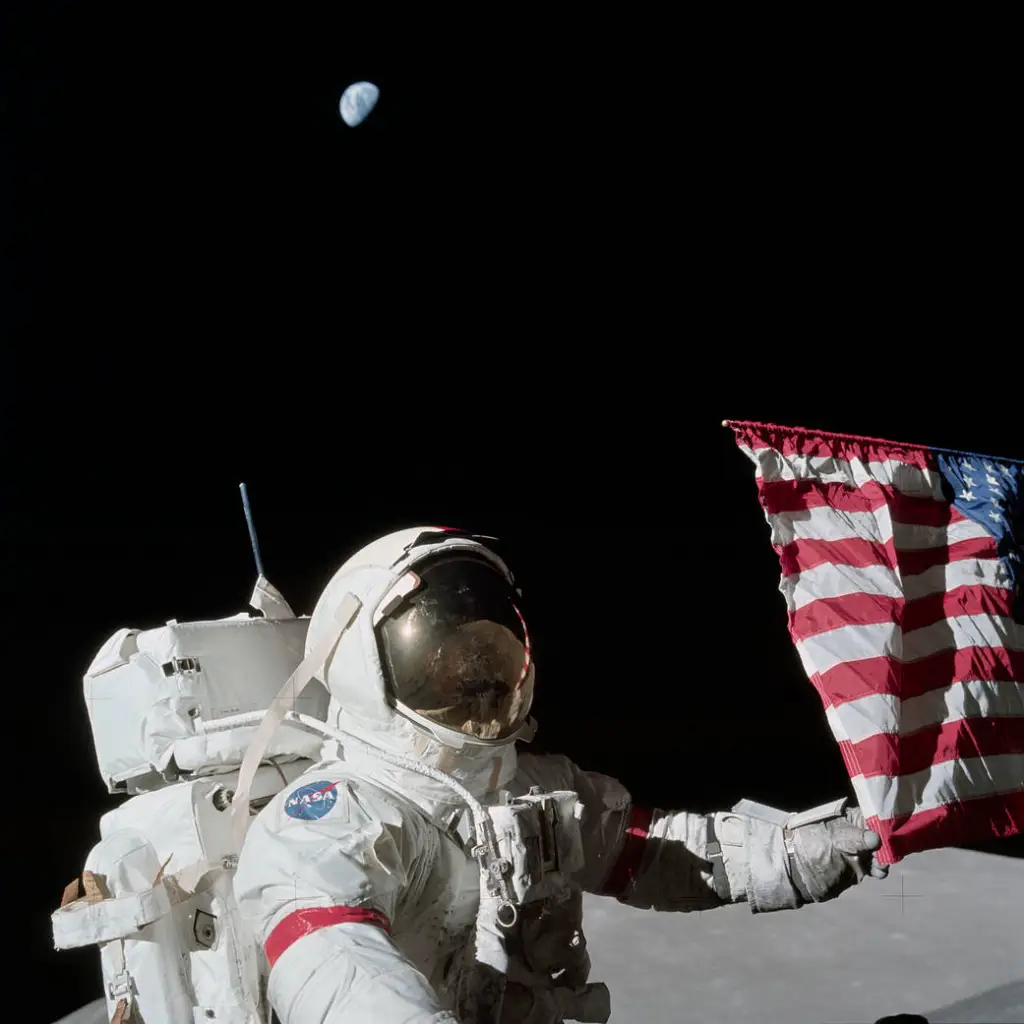

Surely, moon landings are always a thrill. The descent of Japan’s SLIM probe (complications and all) was inspiring, India’s Chandrayaan-3 mission rippled voltaic moments of its own, capturing the hearts of many across the world, and filmmakers are still making movies about the Apollo years. But there’s something special about Odysseus.

With this landing, Odysseus is officially the first private spacecraft to ever achieve the feat. It’s also the first American module to stand on the moon’s cratered body in over half a century. The last time a US-borne probe got to Earth’s reflective companion, it was 1972. And alongside these honors, Odysseus managed to carve out a very important place in humanity’s upcoming lunar odyssey — it proved that commercial lunar landings can work, and it suggests we’re about to see way more of them.

Related: Who Owns the Moon? | Space Law & Outer Space Treaties

But while we’ve all surely caught the moon bug, lunar pioneers will soon need to contend with a pretty serious issue when it comes to space exploration.

“The thing about space is there is very little law,” Martin Elvis, an astrophysicist at the Harvard & Smithsonian’s Center for Astrophysics, said during this year’s American Astronomical Society meeting.

As Elvis says, the only firm type of space rulebook we have right now is the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, which outlines tenets such as “states shall be liable for damage caused by their space objects” and “states shall avoid harmful contamination of space and celestial bodies.” But even that has its caveats.

“It’s not a prescription of laws,” Elvis said. “It’s a set of principles.”

Is space technically a free-for-all?

It should be noted that policymakers are indeed making strides toward laying out the ground rules as nations across the globe start racing to space with wide dreams of moon mining, lunar telescope building and even placing artistic marks on the lunar surface. You may also find it interesting that there apparently seems to be an aspiration of sending Bitcoin and NFTs to the moon as well.

The Artemis Accords, for one, is a US-led endeavor to get as many space-curious countries as possible to agree on peaceful exploration. It’s named for NASA’s ambitious Artemis program, which aims to get boots on the moon within the next couple of years — and on Mars someday, too. However, the Artemis Accords are also technically non-binding. Even if they provide a helpful framework for the day on which space laws are finally written, they’re not laws.

“If you pick up a rock and put it in a bag, it’s yours,” Elvis said of one Artemis Accords rule. “It belongs to the agency or the state that did that.”

This principle, to be fair, has already proven true to great degree as we’ve seen with the Apollo moon samples, Japan’s Hayabusa2 asteroid samples and most recently, NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission asteroid samples. As Elvis puts it, “it’s a de facto thing.”

“The other change it introduces is to come up with the idea of safety zones around different installations,” he said. Though the astrophysicist admits he’s written a paper before about how this idea could be “terribly misused” to claim property on the moon, he emphasizes it’s a good idea in general. Still, what sticks out is the fact that none of this is written law.

“In terms of governance of the moon right now, there is none essentially,” Elvis said, though on the bright side, “there are ongoing approaches to develop laws for the moon.”

The United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Space exists, for instance, an organization that meets rather often to discuss how to promote non-violent space exploration. According to the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs, the last meeting ran this year from Jan. 29 to Feb. 9. “There is a group called For All Mankind,” Elvis added, “which is trying to protect landing sites and other historical sites on the moon.” There’s also the very interesting fact that, in 2022, Canada extended its criminal law jurisdiction to the moon.

Yet, with the success of Odysseus, we now know that both space agencies and non-space agencies can start populating the moon with various things they wish to send up there. Private companies may have their own set of criteria for stuff they’re willing to blast toward the moon (Intuitive Machines requires that you fill out a form, for instance), but I suppose that’d be up to each company’s discretion. Might this be the push that was needed to get some lunar laws (like, real laws) etched into something more solid?

In fact, the biggest reason Odysseus is on the moon right now is thanks to NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services program, or CLPS. The agency basically created this program because it wanted a way to enlist private companies to take care of transit to the moon (aka, make the rocket and lander) so that its science experiments can just be the passengers. And even if NASA gets to reserve a few first class spots on the trip, other people can pay to have their science equipment onboard as well — and it doesn’t even need to be science equipment.

Artist Jeff Koons, for instance, sent one of his art installations to the moon via Odysseus next to an “indestructible” time capsule meant to preserve human knowledge on the lunar surface. (That’s not worrying to think about at all; the end of humanity on Earth.) Down the line, we may even start seeing CLPS missions bring components, piece by piece, for some pretty grand lunar scientific endeavors.

It could get crowded up there far sooner than we once imagined; we’ve already seen it happen with satellites in low Earth orbit.

The price of putting something in our planet’s gravitational tides has become based on the market value of those tides, a value dictated by demand. Some have even devised strategies of throwing things into a cheaper area of Earth’s orbit first, then forcing the device to change orbits later on. Theoretically, they argue, that should circumvent high costs. Will the same thing happen on the moon?

Competing for lunar real estate

Despite commercial companies now being able to ferry their goods to the lunar surface, Elvis and fellow lunar ethics expert Alanna Krolikowski are primarily focused on pushing for science-related moon laws.

The simple reason is that science investigations are usually highly specific based on what equipment is available and what signals you’re trying to track. Even in a laboratory on Earth, you need to worry about temperature, humidity, and other stuff when designing the perfect room for experimentation.

But on a cosmic scale, if you want infrared signals, for instance, you can’t have infrared interference; that’s why the James Webb Space Telescope is located at L2 with a hefty silver sunshield. The sun creates major infrared interference, but that spot is quite protected because it sits on the side of Earth opposite the sun at all times.

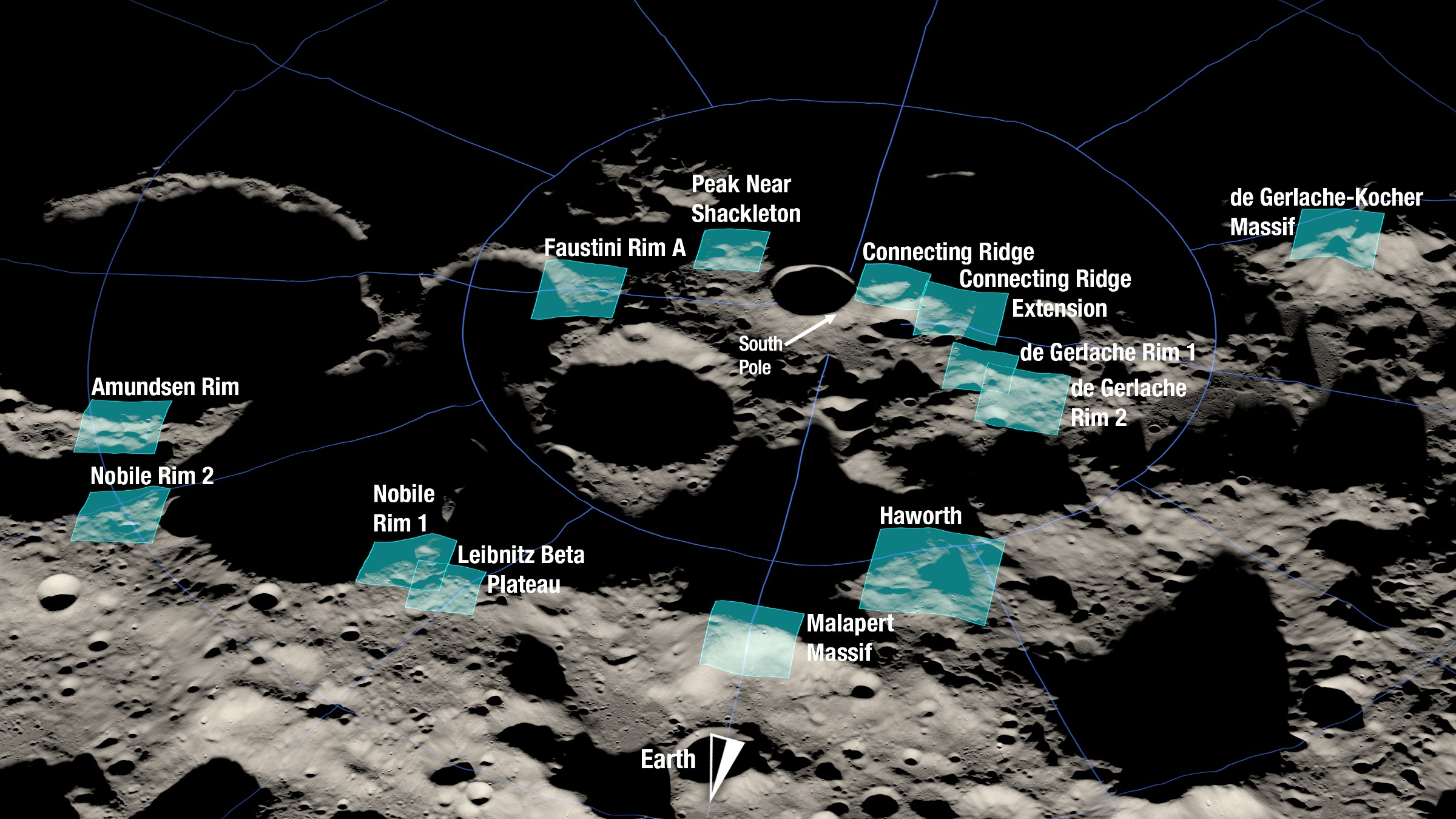

Similarly, on the moon, any planned observatories will want to be in specific locations. And specificity like this, inevitably, can cause competition. Take moon mining.

“Helium-3 mining has been mentioned on the moon as a source of fusion power,” Elvis said, though he followed that up quickly by saying he thinks it’s a bit of a moot point as we don’t have any fusion reactors yet to play with. “It’s going to be a long time before we get one that burns Helium-3,” he explained.

On the other hand, however, Helium-3 is believed to be a valuable substance for quantum computing — a burgeoning field that allows computer hardware to dip into the quantum realm and achieve mind-bending levels of computing power. Engineers are still working out the crevices of that whole endeavor, but they’re definitely trudging along. “If that turns out to be necessary,” Elvis said, “then there will be a huge market.”

And all that Helium-3 mining, obviously, must be done in Helium-3-rich locations on the moon. Thankfully, according to Elvis’ calculations, there exists some Helium-3 mining sites that fall on the far side of the moon. This means, from Earth, if lunar miners decide to run operations there, we probably won’t see our beloved celestial friend marred by construction efforts. “There won’t be any nasty scars to be seen from your balcony,” Elvis said.

But would any of this pose an issue if the best Helium-3 mining sites happen to fall in the same location as the best zone in which to conduct infrared astronomy? Will they be too close to areas where gravitational wave detectors may one day be built, therefore introducing seismic interference with all the drilling?

“We have a fundamental problem in this case,” Elvis said. “Perhaps of a clash between the astronomical value and the scientific value of the site versus dollar value.”

For instance, the Lunar Labs Initiative at Vanderbilt University is working on the blueprints for building a gravitational wave detector on the moon, meaning it can’t be positioned near any drilling sites. And that doesn’t just go for Helium-3 drilling — some areas on the moon are believed to be “wet,” or hold water content that space agencies hope to access. Plus, if these agencies do indeed access that water, it wouldn’t be far-fetched to imagine they’d build a base around those oases.

Elvis also points out the envisaged LION gravitational wave telescope concept, which stands for “laser interferometer on the moon.” Based on this observatory’s blueprints, it’d need to be in cold areas of the lunar surface to work. Elvis picked out three good craters within which he suggests it can be built. “You need to find an abundantly shadowed region with these very cold traps in the middle,” he said. “There are really only three.” And of the three — Haworth, Shoemaker and Faustini — only Faustini is dry.

That may create some rivalry for future infrared moon astronomers. “For the infrared telescopes,” he said, “you want to get to the longest wavelengths; you want to be in the coldest of the cold traps.”

“I don’t think we should completely shut down the use of the moon,” he added. “It’s tricky — it’s not going to be a yes or no — it’s going to be a matter of careful deliberation and negotiation.”

Furthermore, all of this isn’t to say commercial lunar goals aren’t a worry as well — especially for large enterprise projects. “There were even ideas for building or bulldozing patterns into the moon’s surface that would advertise the Nike swoosh,” Elvis said. “That would be like an abomination in my humble opinion.”

It’s also worth considering the recent controversy that appeared when Astrobotic’s Peregrine lander, aka NASA’s first CLPS try (and failure), carried human ashes on its lunar journey. The Navajo Nation objected, asking NASA to prevent the ashes from reaching the moon’s surface as the celestial object is sacred to Indigenous culture. “There are certainly groups of people who are reasonably vocal about protecting the moon, or at least the appearance of the moon on the near side,” Elvis said. “It’s something that all of humankind shares.

“We’ve always seen the moon untouched and unblemished.”

So, to keep it that way, it may be time to consider the ethics of lunar exploration — and consider how we can turn those ethics into actionable laws.