On Oct. 14, NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft began a vital mission. It will be investigating the potential habitability of Jupiter’s icy ocean moon Europa — but first, it has to get there.

Though not on an “alien hunting” mission, as some have described it, there’s no doubt that the Europa Clipper is an important step forward in our understanding of life elsewhere in the solar system. Europa is thought to harbor some of the essential elements for life under its thick and icy shell, including complex chemicals and water, so the Europa Clipper is tasked with decoding the habitability conditions of this Jovian moon. In doing so, it will help scientists better plan for missions that may have the potential to indeed hunt for living things, even if only by eliminating a once promising target.

“The mission’s three main science objectives are to understand the nature of the ice shell and the ocean beneath it, along with the moon’s composition and geology,” NASA writes on its Europa Clipper Mission website. “The mission’s detailed exploration of Europa will help scientists better understand the astrobiological potential for habitable worlds beyond our planet.”

But it isn’t all plain sailing now that the Europa Clipper has left Earth. The journey to the Jovian system is imposing, with the gas giant sitting an average of 444 million miles (778 million kilometers) away from Earth. Plus, the $6 billion spacecraft won’t be taking a straight shot to the gas giant.

By the time the NASA craft reaches the Jovian system in April of 2030, it will have traveled at least 1.8 billion miles (2.9 billion km), according to the space agency.

Here is what the itinerary looks like.

A grand tour of the solar system

For the Europa Clipper to reach Jupiter and enter the kind of orbit it needs to probe Europa, it will need to make several flybys of other solar system planets. That will include Earth — or at least the region of space around our planet that can provide a “gravity assist.”

Now that it has launched, the next major milestone for the spacecraft will be a flyby of Mars on March 1, 2025. During this maneuver, the spacecraft will get as close as 300 miles and 600 miles (482 to 965 kilometers) above Mars’ surface.

This gravity assist won’t send the Europa Clipper on to Jupiter, however. Instead, that’s when it comes back toward Earth.

The NASA spacecraft will be home in time for Christmas in 2026, making a flyby of our planet on Dec. 3 that year. This will be a literal flying visit (no pun intended) that will see the spacecraft come no closer to Earth than around 2,000 miles (3,200 kilometers) and quickly depart for good. This will give the Europa Clipper enough energy to set a course for Jupiter at last.

Reaching the Jovian system in 2030, the orbiter will fire its engines to slow its approach to the gas giant and associated moons. NASA says that this process will take around six hours. As it is braking, the Europa Clipper will make its first flyby of a Jovian moon. This won’t be Europa, but rather the largest moon in the solar system: Ganymede.

The flyby of Ganymede and several other Jovian moons will reduce the orbit of the Europa Clipper and bring it into sync with its final target, Europa. The spacecraft will make a flyby of this icy ocean world in the spring of 2031, with its science campaign kicking off in May of the same year. Over the next three years, the spacecraft will make 49 flybys of Europa using its suite of nine instruments to collect data regarding the conditions of the icy moon.

At this point, you may wonder: There are a few icy ocean moons in the solar system, such as Saturn’s moon Enceladus, that could have the right stuff for life, so why has NASA selected Europa as its focus?

Europa has a lot going for it

Well, based on what we know about the conditions needed to support life on Earth, Europa really seems to have the right stuff for habitability.

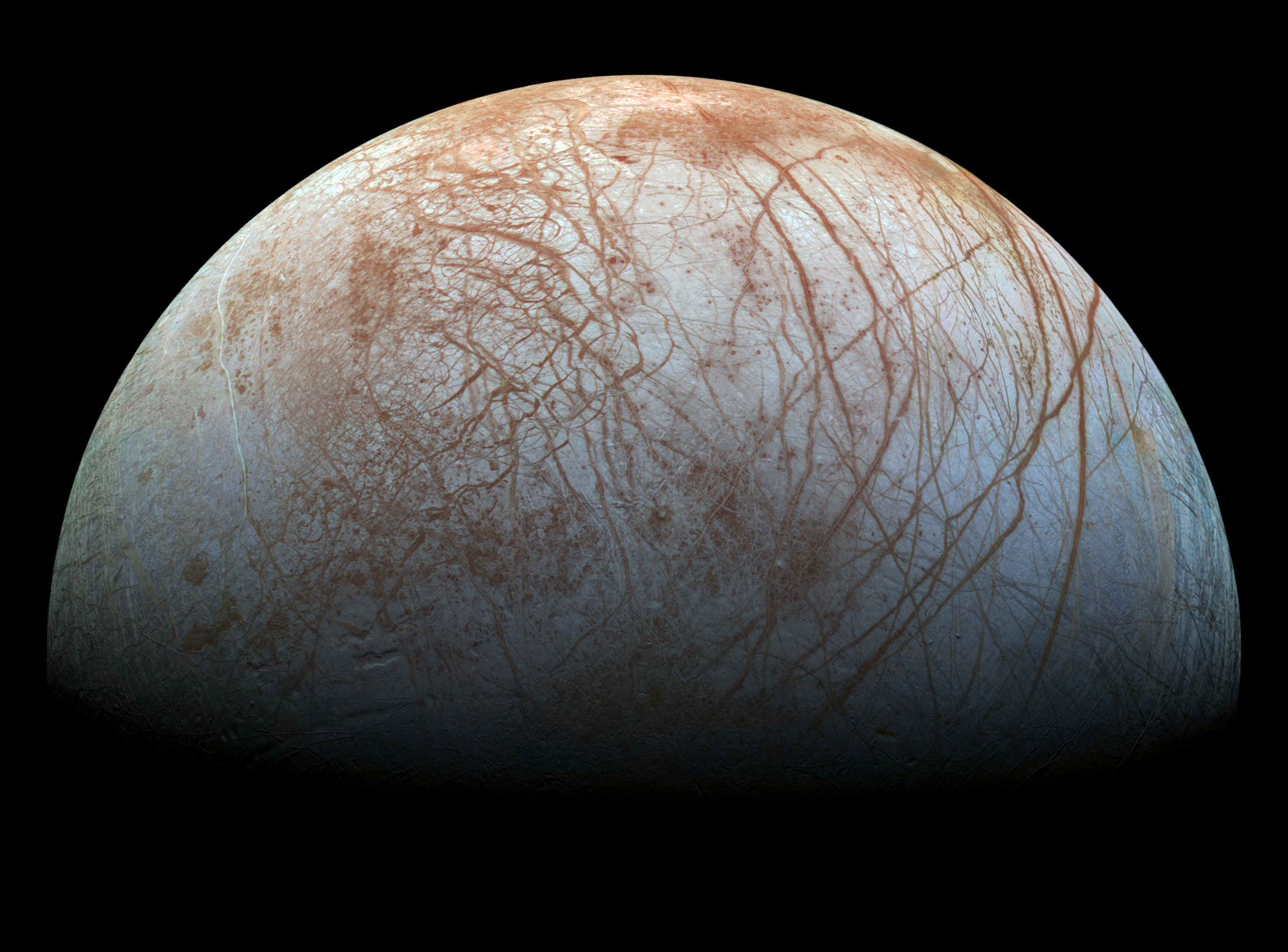

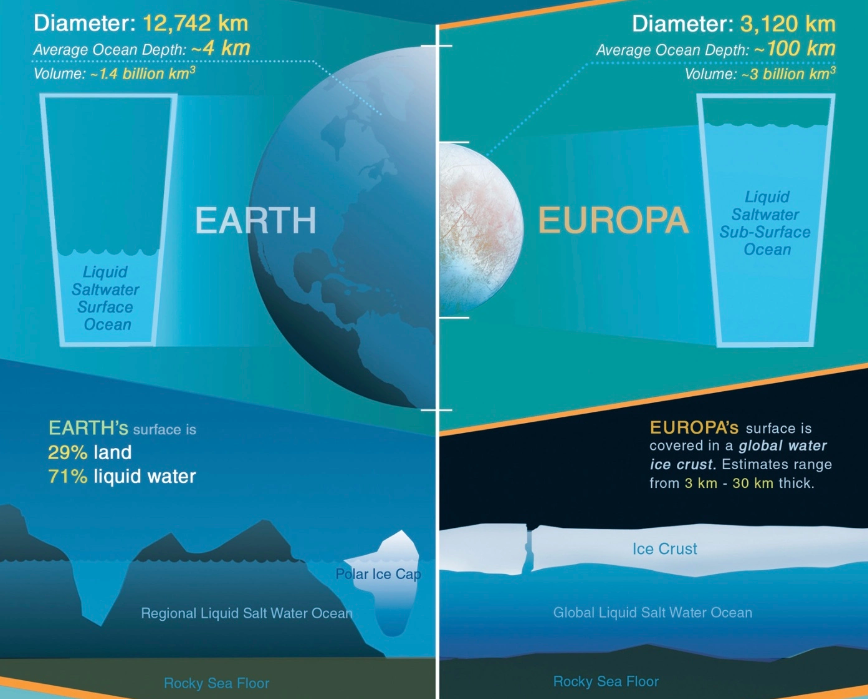

Firstly, the characteristics of Europa strongly suggest a subsurface ocean exists under the 2-mile- to 19-mile- (3-kilometer- to 30-kilometer-) thick, icy shell of this Jovian moon.

That ocean of liquid water is thought to be global with an estimated average depth of 62 miles (100 km). For comparison, Earth’s oceans have an average depth of around 2.5 miles (4 km). And it isn’t just the abundance of water on Europa that makes it a promising target for habitability studies.

Life needs certain chemical elements for its “building blocks” to form, including carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus and sulfur. These come together to form so-called “organic molecules,” which are essential to life and comprise 98% of the living matter here on Earth. Researchers theorize these elements were likely incorporated into Europa as the Jovian moon formed.

After its birth, additional organic molecules are thought to have been delivered to Europa via asteroids and comets that slammed into its surface, similar to how scientists theorize that asteroids delivered many of the ingredients needed for life to Earth.

Living things also need food, no matter how simple they are, and Europa could provide this via the weathering of its rocky interior.

“Water dissolves nutrients for organisms to eat, transports important chemicals within living cells, supports metabolism and allows those cells to get rid of waste,” NASA states on its Europa website. “Scientists are confident there’s a rocky seafloor at the bottom of Europa’s ocean. Hydrothermal activity could possibly supply chemical nutrients that could support living organisms.”

And there’s more: Living things need energy, too. This is provided by Jupiter and the gas giant planet’s gravitational influence.

That influence generates powerful tidal forces that cause Europa’s rocky interior to “flex,” releasing chemicals and also heating its oceans. Additional energy is supplied in the form of radiation from Jupiter, which would be a death sentence for simple life at the surface of Europa. Under the moon’s protective ice shell, however, filtered radiation could actually be a fuel source for ocean-dwelling organisms.

Currently, the Europa Clipper is set to cease operations in September of 2034, just under a decade after its launch. The spacecraft will be deorbited and sent plunging into the surface of Ganymede.

By then, the data the spacecraft has collected during its decade-long lifetime may have brought humanity tantalizingly close to finally answering the question of whether life exists beyond Earth.